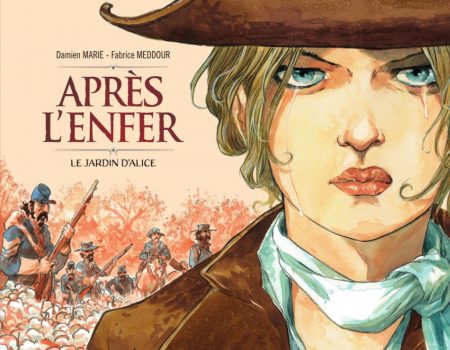

Poucas coisas afetam mais nossa experiência com um jogo histórico do que os uniformes que vestimos – metaforicamente – quanto sentamos à mesa. Uma mesma jogatina pode ser uma experiência inspiradora ou horripilante dependendo da facção que controlarmos.

Poucas coisas afetam mais nossa experiência com um jogo histórico do que os uniformes que vestimos – metaforicamente – quanto sentamos à mesa. Uma mesma jogatina pode ser uma experiência inspiradora ou horripilante dependendo da facção que controlarmos.

Um wargame jogado do ponto de vista do vencedor nos convida a repetir os passos de alguma operação icônica. O mesmo jogo visto pelos olhos do perdedor é um ato de rebeldia contra a inevitabilidade da história.

Um jogo de estratégia 4X pode ser uma fantasia de poder se controlarmos generais ou imperadores – ou uma história de terror se experimentada pelos conquistados.

Desde o princípio, portanto, sabíamos que o tom de Os Triunfos de Tarlac seria dado pelas facções que permitíssemos aos jogadores encarnar.

De todas as escolhas que teríamos que tomar, esta era uma das que menos dava margem para erros. Isto porque ela ditaria todas as decisões criativas a partir daí.

Mas, afinal, o que é uma “facção”?

A questão é mais complicada do que parece. Na vida real, raramente trombamos com “facções” bem-delineadas fora de um estádio de futebol ou de um bar no final de um campeonato. Por mais que façamos parte de grupos de interesse – o que nos confere, às vezes, desvantagens ou privilégios – a sociedade humana é bem diferente de uma colmeia em que todos pensam e agem da mesma forma.

Historiadores, acostumados a enxergar o passado através da lente de povos, nações e movimentos, às vezes esquecem que por trás desses grupos existem indivíduos com vontade própria. Este é um vício que jogos de estratégia amiúde perpetuam, dividindo o mundo em nacionalidades – “Os Ingleses”, “Os Mongóis” – ou países – “O Brasil”, “O Império Britânico” – como se fossem peças indivisíveis.

Por outro lado, não dá para negar que entidades coletivas às vezes apresentam comportamentos agregados.

Instituições, estados, partidos políticos, regimentos de um exército – para citar apenas alguns exemplos – têm objetivos e condutas que falam mais alto que a soma das ações de seus membros. Não só isto, estes grupos possuem uma incrível capacidade de condicionar seus membros a agir da maneira que gostariam.

Como belamente descreveu o escritor Stephan Crane, em seu clássico A Glória de um Covarde,

“[O soldado] subitamente deixou de se preocupar consigo mesmo e esqueceu de encarar um destino ameaçador. Ele se tornou não um homem, mas um membro. Ele sentiu que alguma coisa de que ele era parte – um regimento, um exército, uma causa ou um país – estava em crise. Ele foi fundido a uma personalidade comum que fora dominada por um único desejo. Por alguns momentos ele não pôde fugir mais do que um dedo mindinho pode cometer uma revolução contra uma mão”.

Navegar esse dilema é uma coisa que todo desenvolvedor de jogos históricos precisa fazer.

Focar demais em grupos e instituições pode nos levar a apagar a agência de indivíduos – quando não a de grupos minoritários inteiros que não participavam diretamente do exercício do poder.

Focar demais em indivíduos, por outro lado, pode nos induzir a julgar a história por suas exceções, um eterno jogo de caprichos pessoais que não obedece a qualquer lógica.

Mas há uma terceira armadilha em desenvolver facções que só descobrimos quando resolvemos testar nosso próprio jogo.

O problema das facções em Os Triunfos de Tarlac

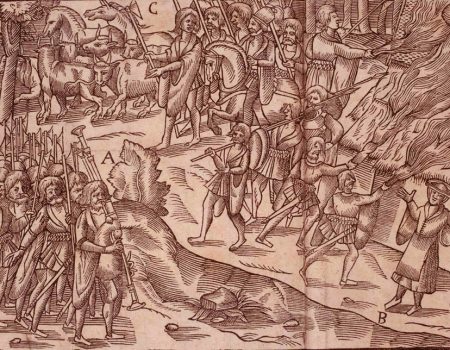

Antes de falar do impasse a que chegamos, é útil falar um um pouquinho do nosso cenário – e da hierarquia de poder que existia na época que retrata. O reino Thomond nos séculos XIII e XIV, afinal de contas, estava longe de ser um reino unificado.

No topo da pirâmide estavam os ingleses da família de Clare, a quem a Coroa da Inglaterra havia cedido a liberty[1] de Thomond.

Num segundo nível, estava o rei gaélico de Thomond, tradicionalmente pertencente à dinastia dos Uí Bhriain. Como expliquei no meu primeiro diário, na época em que se passa Os Triunfos de Tarlac, os Uí Bhriain estavam divididos entre dois clãs em guerra um com o outro: o Clã Tarlac e o Clã Brian Rua

Em terceiro lugar estava uma constelação de reis menores, a maioria deles vassalos do rei gaélico de Thomond.

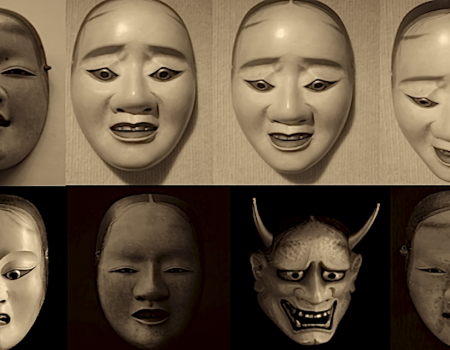

Hierarquia das facções em “Os Triunfos de Tarlac”

Nossa ideia inicial era que cada uma dessas unidades políticas fosse controlada por um jogador diferente. Desta maneira, alguém controlaria os de Clare; duas pessoas controlariam os Clãs Tarlac e Brian Rua, respectivamente, e o restante dos jogadores se dividiria entre os reinos vassalos.

A vantagem dessa divisão é que ela era simples o suficiente para ser representada no jogo, mas ainda assim respeitava o princípio de que o poder político era fundamentalmente capilarizado.

É impossível conseguir tributo e soldados sem a cooperação de seus vassalos. Contudo, estes vassalos são controlados por outros jogadores, que podem decidir não obedecer – ou pior, fracassar em fazê-lo. E é super difícil obter esta cooperação quando há oponentes no tabuleiro dando o seu melhor para que ela não aconteça.

O problema: não tinha graça nenhuma

Foi preciso quase um ano de testes até notarmos que havia algo de podre no reino de Thomond.

Depois de muito penar (sem sucesso) para tornar nosso jogo mais divertido, notamos que a qualidade da experiência dos jogadores variava brutalmente dependendo da facção que escolhiam.

Aqueles que jogavam com as facções no “topo” da pirâmide política –Clã Tarlac, Clã Brian Rua ou os ingleses – se divertiam de monte.

Aqueles que controlavam reis menores, por outro lado, experimentavam um tédio sem fim. Não eram raros casos em que jogos inteiros começavam e terminados sem que estes jogadores jogassem mais do que alguns minutos.

Como o destino dessas facções não tem influência direta sobre a duração dos turnos – uma rodada pode continuar indefinidamente desde que os dois clãs principais continuem no páreo — também acontecia de jogadores serem eliminados logo de início e terem de esperar uma rodada inteira para voltarem a jogar.

Considerando que nossas rodadas às vezes se estendiam por mais de meia hora, é muito tempo para ficar sentado sem fazer nada.

O problema é que não havia muito o que fazer. Como eu escrevi em um diário anterior, a rotina de um rei medieval podia ser terrivelmente repetitiva e entendiante. Jogos comerciais se esquivam desse problema dando a estas facções objetivos irrealistas ou poderes maiores do que eles gozavam na época. Porém, isto não era algo que podíamos fazer sem sacrificar nosso comprometimento com a precisão histórica.

Sem essas ferramentas para “apimentar” a jogo, tivemos de adotar uma solução mais simples: alterar nossa escala de abstração.

As três facções “divertidas” de se jogar – os clãs principais, os ingleses – continuariam como estavam.

Os reis menores, por outro lado, seriam agrupados em duas super-facções: os aliados do Clã Tarlac e os aliados do Clã Brian Rua.

Segundo esse novo sistema, os jogadores que não controlam as facções principais contam com muito mais responsabilidade. Se antes eles podiam passar partidas inteiras participando ativamente por poucos minutos, o novo arranjo dá a eles o poder de, literalmente, virar o jogo. Somados, a metade dos reinos menores de Thomond são mais fortes que seu suseranos, ou mesmo os ingleses.

Mais: é muito mais difícil para um jogador ser eliminado logo de cara, ainda que ele sofra uma sequência catastrófica de má sorte. Com oito reinos menores espalhados pelo tabuleiro, é quase sempre possível ter pelo menos uma base restante com que se mobilizar. E, caso não é tenha, é provável que o mapa já esteja tão dilapidado que o fim da rodada chegará logo de uma maneira ou de outra.

O esquema não é tão bom quanto nossa ideia anterior para representar a capilaridade do poder político. Embora os jogadores que controlem os clãs principais ainda precisem da cooperação de seus vassalos, é incomparavelmente mais fácil coordenar os movimentos com um jogador do que com um pequeno grupo.

Mas essa limitação não afeta tanto as coisas, já que as regras de mobilização militar, como mencionei em outro diário, são bastante restritivas – e vulneráveis à sabotagem de oponentes.

Gameplay emergente e mais

Curiosamente, esse novo arranjo também permite que os jogadores expandam seus domínios de uma maneira que as regras originais não contemplavam.

Como explicarei em um próximo diário, dedicado às regras de diplomacia, nem todas as facções começam alinhadas com Clã Tarlac e Clã Brian Rua no início do jogo. Certos reinos começam oficialmente neutros, e devem ser convocados pelos pretendentes em guerra antes de tomar parte no conflito.

Em termos práticos, cada facção neutra convocada dessa forma passa a ser controlada pelo jogador responsável pelos reinos menores, efetivamente aumentando seu poder – e, indiretamente, o poder do clã principal a que está aliado.

Isso é interessante de uma perspectiva lúdica, pois permite que o jogo apresente alguma dose de gameplay emergente – a capacidade das regras serem combinadas ou exploradas de tal maneira que produzam situações imprevisíveis.

Ao mesmo tempo, permitir que facções sejam “agrupadas” dá ao jogo uma maior flexibilidade para acomodar números diferentes de jogadores.

Com 5 jogadores (número que considero ideal), duas pessoas controlam cada uma um clã dos Uí Bhriain (Tarlac e Brian Rua), outros dois jogadores controlam seus aliados e um quinto participante controla os ingleses.

Grupos maiores, contudo, podem “quebrar” as facções de aliados em duas, permitindo que até sete pessoas integrem à mesa – embora, obviamente, corram o risco de protagonizar apenas metade da ação.

Da mesma forma, caso faltem pessoas à jogatina, os Clãs Tarlac e Brian Rua podem ser agrupados com seus aliados em uma única super-facção, permitindo que o jogo seja jogado por grupos apenas três jogadores.

Alguma coisa obviamente se perde nessas montagens alternativas: ao controlar todos os aliados, vai-se pela janela a tensão de depender das ações de outros jogadores. Ao mesmo tempo, ela pode ser interessante para professores que desejem utilizar o Tarlac em sala de aula.

Levará algum tempo para sabermos se a idea funciona. Felizmente, nós não temos mais de fazer isto sozinho. Os Triunfos de Tarlac acabou de entrar em uma fase aberta de testes, o que significa que começaremos a receber feedback de outros historiadores e desenvolvedores de jogos.

Grandes mudanças vêm pela frente – e eu estarei aqui para escrever sobre todas elas!

[1] Liberty era um tipo de concessão de terra que isentava quem a recebia de prestar contas à Coroa. Os líderes destas terras tinham a liberdade para operar sua própria administração local, o que lhes dava grande independência.

Few things affect our experience with a historical game more than the uniforms we wear (metaphorically speaking) when we sit at the table. A single playthrough may turn out to be an empowering or bloodcurdling affair depending on which faction we control.

A wargame played from the point of view of the winner invites us to retrace the steps of an iconic operation. The same game seen through the eyes of the loser becomes an act of rebellion against historical inevitability.

A 4X strategy game can be a power fantasy if we take the role of generals or emperors – or a horror story if experienced by those who were conquered.

From the very beginning, therefore, we knew that the tone of The Triumphs of Turloughs would be set by the factions we’d let players embody.

From all the choices we had to make, this was one of those that allowed the least room for mistakes. This is because it would dictate all of our creative decisions from that point on.

But what is a ‘faction’, after all?

The question is more complicated than it seems. In real life, we rarely stumble upon clear-cut “factions” outside of a soccer stadium or a pub by the end of a sport championship. Even though each of us belongs to interest groups – something that, at times, grants us disadvantages or privileges – human society is very different from a hive in which everyone think and act in the same way.

Historians, used to seeing the past through the lens of peoples, nations and movements, sometimes forget that behind these groups are free-thinking individuals. This is a shortcoming that strategy games often replicate, dividing the world in nationalities – “The English”, “The Mongols” – or countries – “Brazil”, “The British Empire” – as if they were indivisible entities.

On the other hand, one cannot deny that collective bodies sometimes exhibit aggregate behavior.

Institutions, states, political parties, army regiments – to cite only a few examples – have goals and conducts that speak louder than the sum of the actions of their affiliates. Not only that, these groups also possess an incredible capacity to condition its members to act in the manner they want.

As writer Stephan Crane beautifully described in his war novel The Red Badge of Courage,

“He suddenly lost concern for himself, and forgot to look at a menacing fate. He became not a man but a member. He felt that something of which he was a part— a regiment, an army, a cause, or a country— was in a crisis. He was welded into a common personality which was dominated by a single desire. For some moments he could not flee no more than a little finger can commit a revolution from a hand.”

Navigating this dilemma is something every developer of historical games must learn how to do.

Focusing too much on groups and institutions may lead us to erase individual agency – when not that of entire minority groups that did not directly exercise power.

Focusing too much on individuals, on the other hand, may induce us to judge history by its exceptions, an eternal game of personal whims impervious to logic of any kind.

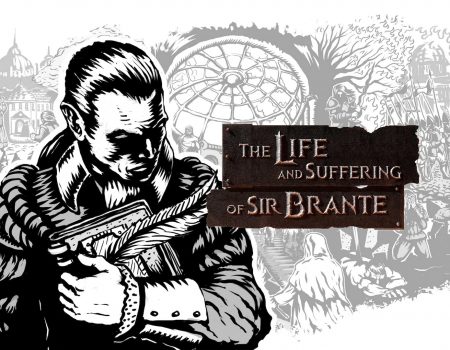

But there is a third trap in developing historical factions that we only stumbled upon when we decided to playtest our own game.

The problem of factions in The Triumphs of Turlough

Before talking about the impasse itself, it might be useful to run by some tidbits of our setting – and the power hierarchy of the period it portrays. The kingdom of Thomond in the 13th and 14tyh centuries, after all, was far from being an unified kingdom.

On the top of the pyramid were the English from the de Clare family, to whom the English Crown had granted the liberty of Thomond.

In the second level was the Irish king of Thomond, who traditionally belonged to the O’Brien dynasty. As I explained in the first diary, during the events of The Triumphs of Turlough the O’Briens were split between two feuding clans: Clann Turlough (also known as Clann Taidhg) and Clann Brian Roe.

In third place were a constellation of petty kings, most of them vassals of the Irish king of Thomond.

Hierarchy of factions in “The Triumphs of Turlough”

Our initial idea was that each of these political unities should be controlled by a different player. In this way, someone would control the de Clares; two persons would control Clann Turlough and Clann Brian Roe, respectively, and the rest of the players would pick the vassal petty kingdoms.

The advantage of this division is that it was simple enough to be represented in the game, but still observed the principle that political power was fundamentally capillarized.

It is impossible to obtain tributes and soldiers without the cooperation of one’s vassals. However, these vassals are controlled by other players, who may opt not to comply with one’s orders – or worse, fail to do so. And it is very difficult to enforce this cooperation when there are opponents around the board giving their best to prevent it from happening.

The problem: this was no fun at all

It took almost a year of testing for us to notice that there was something rotten in the kingdom of Thomond.

After struggling for a long time (and without results) to make our game more fun, we noted that the quality of our players’ experiences differed significantly depending on which faction they chose.

Those who played with the factions at the “top” of the political pyramid – Clann Turlough, Clann Brian Roe, the de Clares – were having the time of their lives.

Those who controlled petty kings, on the other hand, were bored out of their minds. It wasn’t uncommon for entire matches to start and end without giving these players the opportunity to play for more than a few minutes.

Since the fate of these factions didn’t directly impact the duration of the turns – a round could continue indefinitely as long as the two main clans were still up and running – sometimes players were eliminated early on and had to wait an entire round to pass to get back in the game.

Given that our rounds sometimes lasted over half an hour, it was too long a break to put our players through.

The problem is there wasn’t much we could do. As I wrote in a previous diary, the routine of a medieval king could be terribly repetitive and boring. Commercial games get around this problem by giving these factions unrealistic objectives or levels of power far greater than they enjoyed in the period. However, this wasn’t something we could do without relinquishing our commitment to historical accuracy.

Without these subterfuges to “spice” things up, we had to adopt a simpler solution: changing our scale of abstraction.

The three “fun” factions – the main clans, the English – would remain as they were.

The lesser kings, on the other hand, would be grouped into two super-factions: the allies of Clann Turlough and the allies of Clann Brian Roe.

According to this new system, the players that did not control the main factions now would have much more on their plates. If they could spend entire matches actively participating for just a few minutes, now they had the power to, quite literally, turn the game upside down. Together, even half of the petty kingdoms of Thomond were stronger than their lieges, or even the English.

In addition, it is far more difficult for a player to be eliminated from the get go, even if they suffer a catastrophic string of bad luck. With eight petty kingdoms scattered around the board, it is almost always possible to have at least one remaining base from which to mobilize. And, in case there isn’t one, it is likely the map is already so dilapidated that the end of the round is imminent one way or the other.

This scheme is not as good as our previous idea to represent the capillarity of political power. While the controllers of the main clans still need the cooperation from their vassals, it is incomparably easier to coordinate your movements with a single player than a small coalition.

But this limitation should not (we hope) affect things too much, since the military mobilization rules, as I mentioned in a previous diary – are quite restrictive – and vulnerable to sabotage by opponents.

Emergent gameplay and more

Interestingly, this new scheme also allows players to expand their territories in a way the original rules didn’t contemplate.

As I will explain in a future, diplomacy-themed diary, not all factions start aligned with Clann Turlough or Clann Brian Roe at the beginning of the game. Certain kingdoms start from a position of neutrality and must be summoned by the belligerent claimants before they can take part in the conflict.

In practical terms, each neutral faction summoned in this fashion becomes a playable faction under the control of whoever controls the lesser kingdoms and gets to it first, effectively increasing their holdings – and, indirectly, the power of the main clan to which they are allied.

This is interesting from a ludic perspective, as it gives the game some measure of emergent gameplay – the capacity to combine or explore rules in such ways that arrive at unpredictable outcomes.

At the same time, allowing factions to be merged provides the game more flexibility to accommodate different numbers of players.

With 5 players (a number I consider ideal), two persons control one of the O’Brien clans (Turlough and Brian Roe) each, two other players control their allies, and a fifth controls the English.

Smaller groups, however, can “break up” the allies’ factions in two, allowing up to seven people to join the match – although they obviously risk seeing only half the action.

In the same way, if there are not enough people to play, clans Turlough and Brian Roe can be grouped with their respective allies in a single super-faction, making it possible for as little as three players to play the game.

Something will obviously be lacking in these alternative setups. By controlling all of one’s allies as well as one’s faction, the whole stress of depending on the actions of others goes out of the window. At the same time, this could be interesting to teachers who wish to use Turlough in the classroom. It’s sometimes easier to break up a class in groups of three, and a limited number of players will also make play sessions shorter.

It will take some time for us to determine if the idea works. Fortunately, we don’t have to do that by ourselves anymore. The Triumphs of Turlough has just entered an open testing phase, which means we’ll start receiving feedback from a number of selected historians and game enthusiasts.

Great changes lie ahead – and I’ll be here to write about all of them!

Comentários