Esse post é parte de uma série. Para ler os artigos anteriores, clique aqui.

Imagem destacada: Cálice de Ardagh, da coleção do Museu Nacional da Irlanda. Este artefato medieval foi a inspiração da taça Sam Maguire, entregue atualmente ao vencedor do campeonato sênior de futebol gaélico da Irlanda. Foto de Rihani.

Jogos não são feitos apenas de regras, miniaturas impressionantes ou tabuleiros com artes chamativas. Embora existam muitas definições do que seja um “game” – para Sid Meier de Civilization, ele seria nada além de uma “série de decisões interessante” – muitas delas incluem dois pontos fundamentais: meios de se ganhar – e/ou, de se perder.

Condições de vitória e de derrota podem parecer coisas triviais. Do ponto de vista do design de games, porém, elas são tudo menos isso. O desafio é dobrado em jogos históricos, que precisam equilibrar o imperativo de divertir com objetivos que fariam sentido aos povos do passado.

Como o historiador Robert Houghton certa vez apontou, é justamente aí que muitos games comerciais pisam na bola.

Todos aqui conhecemos exemplos de jogos que representam com esmero as sociedades de outrora, mas permitem que jogadores ajam como nenhuma personagem história se comportaria.

Como eu próprío escrevi em outro artigo, muitos jogos de estratégia obedecem à fórmula 4X (explorar, expandir, extrair, exterminar). “Ganhar”, nesses jogos, esta intimamente relacionado a crescer. Muitas vezes, por cima de jogadores ou NPCs mais fracos.

Isso até bate com a ideologia de certos impérios nos séculos XIX e XX. Porém, não pode de maneira alguma ser tomado como uma regra geral para toda a história humana.

O próprio ato de anexar território indiscriminadamente, que esses games tratam como natural, dependia de uma imensa logística, organização militar e vontade política que a maioria dos líderes do passado não tinha – e sequer tinham a intenção de ter.

Na época em que se passa Os Triunfos de Tarlac, por exemplo (anos 1276 a 1318), reis irlandeses governavam províncias minúsculas para os padrões contemporâneos. Thomond, onde se passa o jogo, mal contava com 3,5 mil km2 de área territorial (Sergipe, o menor estado brasileiro, possuí 21,9 mil km2, mais de 6 vezes mais).

Esses governantes contavam com exércitos compostos de poucas centanas de homens, quando muito. Destes, o grosso vinha das contribuições de seus vassalos, que podiam simplesmente se voltar contra o próprio rei se ele tomasse decisões que os desagradassem. Reinos como esse não tinham condições de se envolver em guerras que durassem mais do que alguns meses. Muito menos de expandir indiscriminadamente, absorvendo mais vassalos insubordinados – e, com eles, ainda mais problemas.

“Governar”, nesse contexto, era menos uma questão de conquista e supremacia que de achar um equilíbrio entre exigências que seus súditos estavam dispostos a oferecer e os recursos necessários para dissuadir seus rivais à rebelião.

Pior: essa modalidade de guerra de baixa intensidade quase nunca chegava a qualquer tipo de conclusão. Historicamente, os conflitos entre o Clã Tarlac e Clã Brian Rua pelo domínio de Thomond se estenderam mais ou menos de 1260 até 1350. Foram quase cem anos de guerra com pouquíssimas mudanças significativas nas fronteiras e balança de poder.

Como vender isso a pessoas acostumadas com jogos que nos permite “pintar o mapa” com nossos impérios? Ou, se não isto, a wargames em que a vitória ou a derrota estavam vinculadas a uma única batalha ou campanha?

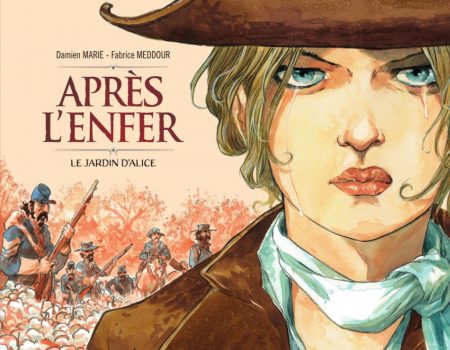

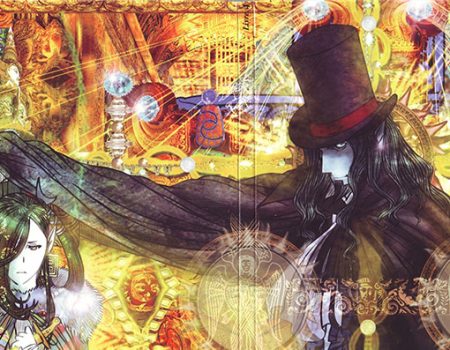

Imagens como essa acima ficaram pendurados (metaforicamente) na minha escrivaninha quando comecei a bolar as regras de Os Triunfos de Tarlac. A solução, ao meu ver, passava por dois desafios. Primeiro, eu precisaria identificar algum desenlace histórico, dentro do horizonte de espectativa desses reis e magnatas, que pudesse ser chamado de “vitória”. Depois, “gamificar” o percurso até ela para que se tornasse minimamente engajante.

Como nossos testes nos ensinaram da maneira mais difícil, nenhuma dessas questões é fácil de responder.

1ª Tentativa: Pontos de febas

Se estimular jogadores a guerrearam uns com os outros poderia enviesar o jogo a uma direção que não desejávamos, por que não premiá-los ao não fazer isso ?

Essa ideia me levou a pensar num sistema de pontuação que recompensasse jogadores por ações historicamente plausíveis. Chamados de febas (em irlandês antigo, “excelência”), esse atributo aumentaria sempre que um jogador fizesse jogadas condizentes a um rei irlandês medieval e diminuiria quando saísse dos trilhos.

Nessa linha, vencer batalhas, reduzir a devastação de assentamentos sob seu controle, manter-se próspero e honrar compromissos aumentaria a febas. Já perder batalhas, ter assentamentos destruídos por outros jogadores e sofrer atos de desobediência a diminuiria.

Ao final do jogo, a coalizão de jogadores que tivesse mais febas – somando os pontos de todos os seus integrantes – seria declarada a vencedora.

Para o jogador que controlasse Thomas de Clare, o magnata inglês em Thomond (e que, como um relativo estrangeiro à política irlandesa, não necessariamente jogava pelas mesmas regras), a situação seria um pouco mais simples.

Historicamente, os de Clare buscaram assegurar sua posição envolvendo-se na guerra entre os Uí Bhriain. Sua presença na região dependia de operações militares regulares e terminou após uma derrota em batalha. Desta maneira, seus objetivos casavam bem com a lógica tradicional dos wargames, e nos permitiu emprestar suas condições de vitória.

Para vencer com os irlandeses, portanto, era preciso acumular pontos de febas. Para vencer com os ingleses, por outro lado, era necessário apoiar uma facção irlandesa na guerra e garantir que eles terminassem o jogo com mais febas que seus inimigos.

Castelo de Bunratty, sede do senhorio de Thomas de Clare

Em teoria, esse sistema parecia ter tudo para dar certo. Além de evitar que jogadores tentassem trair seus aliados e agir anti-socialmente, a vitória por febas permitia que o jogo adquirisse uma duração flexível. Uma partida, afinal, poderia durar tanto quanto as pessoas quisessem: o “placar” podia ser fechado a qualquer momento, seja numa escaramuça de 30 minutos, seja uma campanha épica de 3 dias.

Infelizmente, as coisas não funcionaram tão bem na prática.

Resultado

O que nos parecia a princípio a maior força desse sistema – sua flexibilidade – mostrou-se seu maior problema. Nosso game, reparamos, não tinha condições claras de derrota: era possível “não vencer” ao final da jogatina, nunca ser eliminado do jogo.

Isto, aliado ao fato de não existirem limite de turnos, fez com que as partidas continuassem indefinidamente: os testers não tinham opção senão jogar até se cansarem.

Para piorar, a “vitória”, quando ela enfim chegava, não trazia a menor satisfação. Em um dos casos mais extremos, uma jogadora conseguiu a proeza de vencer uma partida sem fazer absolutamente nada – apenas mantendo distância dos outros jogadores e evitando se envolver em guerras.

Ironicamente, isso fazia sentido histórico. Clímaxes bombásticos e grandes reviravoltas são ingredientes comuns em Hollywood, nem tanto na história humana. Para um rei do século XIII, ser capaz de governar em paz, sem nenhuma preocupação além de ver a grama crescer, era sinal de um grande líder.

Um dos nossos objetivos – fazer nosso jogo tão válido do ponto de vista histórico quanto a tese em que ele é baseado – havia dado certo. O problema, agora, era torná-la divertido.

2ª Tentativa: Vitória da coalizão

Para nossa segunda tentativa, decidimos adotar uma solução mais convencional.

A vitória por febas transformava nosso jogo em uma espécie de “simulador de rei” , o que não casava bem com as mecânicas que havíamos escolhido. Havíamos feito um jogo que não incentivava jogadores a guerrearem, mas em que a única alternativa à guerra era a inação.

Para resolver esse problema, decidimos abandonar a vibe de simulador e se aproximar ainda mais dos wargames. Vencer, portanto, pediria obrigatoriamente uma vitória militar.

Decidimos manter os pontos de febas, só que como condição de derrota. Reveses diplomáticos e derrotas no campo de batalha lentamente reduziriam esse atributo, como uma barra de “pontos de vida” que gradualmente se esgota. Se a febas chegar a zero, é game over.

Febas, assim, representaria o capital político de uma das facções da guerra dinástica em Thomond. Uma (ou três) derrotas em combate pouco faria para determinar um vencedor. Uma série de reveses seguidos, porém, logo convenceria os aristocratas do reino de que aquele cavalo não venceria mais corridas.

Para evitar que o jogo não tivesse fim, ser eliminado em combate implicava na perda imediata de todos os pontos de febas. A intenção era aumentar os riscos das batalhas campais, fazendo jogadores optarem por fugir ou se render diante de uma inimigo mais poderoso, como era o costume na época.

Implementar tudo isso exigiu que tratássemos a diplomacia como um sistema muito mais rígido. Se nas primeiras versões de Tarlac os jogadores eram livres para fazer e desfazer alianças – mediante uma eventual penalidade em febas – nessa versão apoiar sua coalização é a única condição de vitória. Jogadores podiam ser coagidos a mudar de lado cedendo reféns, mas, para ganhar, cedo ou tarde aquele refém precisaria ir embora. Se alguém inicia o jogo como um aliado do Clã Brian Rua, precisa garantir que ele saia por cima. Custe o que custar.

Esse mesma rigidez precisamos aplicar às guerras. Ao contrário das versões iniciais, em que jogadores podiam escolher quando ou se começar uma guerra, o conflito agora se tornava regular e obrigatório. Acabados estavam os dias em que uma tester podia vencer simplesmente ficando na sua e evitando os conflitos na vizinhança.

Resultado

A segunda tentativa funcionou muito melhor. Ainda assim, ela não foi isenta de problemas.

A ideia de transformar a morte em combate em uma condição de derrota foi um imenso tiro pela culatra.

Longe de encorajar jogadores a evitar o combate, essa regra mostrou que era possível vencer o jogo em um só turno. Isto, por sua vez, incentivou os jogadores a apostarem todas as suas fichas na fase de expedição.

O resultado foram jogatinas em que toda a preocupação com a logística – originalmente, o assunto principal do jogo – acabava se tornando um mero prólogo para a batalha.

Como todo o ponto dessas mecânicas era criar obstáculos que aparecessem no longo prazo, isso tornou a fase de manutenção efetivamente, letra morta: por que um jogador tinha de se preocupar com devastação inimiga ou pagamento das tropas se podia mobilizar um exército monstruoso e vencer o jogo naquele mesmo turno?

Felizmente, o jogo melhorou enormemente assim que removemos essa condição de derrota. De quebra, a experiência nos ensinou uma série de verdades contra-intuitivas.

Em primeiro lugar, esses testes nos mostraram que mais amplitude de escolha nem sempre é melhor.

Nas primeiras versões de Tarlac, em que jogadores eram livres para forjar alianças e a vitória independia (nominalmente) de uma guerra, nossos testers se sentiam perdidos. A filosofia “faça o que quiser” não só os impedia de se engajar emocionalmente com o jogo, como tornava difícil até mesmo entender sua lógica. Isso é veneno para um jogo de estratégia, cuja “graça” reside justamente em dominar as mecânicas, antever problemas e gerenciar suas forças de maneiras criativas.

Em segundo lugar, ela nos fez entender, ao menos parcialmente, porque tantos jogos sobre a idade média têm mecânicas relacionadas ao combate.

Em adição ao apelo midiático de cavaleiros em armaduras brilhantes, o combate – e seus proxies – cria cenários de competição direta com que jogadores têm facilidade em se engajar.

No nosso caso, isso nos levou a gradativamente reorientar Tarlac para que o conflito militar ocupasse um lugar de maior destaque do que havíamos antevisto inicialmente.

Isso não significou abandonar nossa proposta original – um game sobre as causas e efeitos da guerra, mais do que sobre a guerra em si. Em especial, a mecânica de devastação funciona como uma rédea para qualquer jogador que chegue ao tabuleiro com ilusões imperialistas.

Devastação é uma propriedade dos assentamentos que aumenta sempre que alguma atividade militar ocorre naquela casa. Este ganho é proporcional ao tamanho dos exércitos: quanto mais soldados um jogador mobiliza, mais rápido transformará seu reino em uma pilha de cinzas.

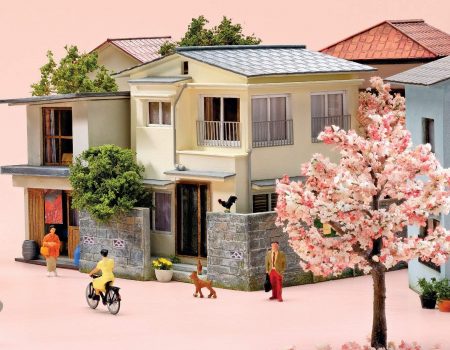

Tokens de devastação no atual protótipo de Tarlac. Pilhas de ponta-cabeça (i.e. com o fundo cinza para cima) representam assentamentos destruídos.

Assentamentos são necessários para alimentar soldados em marcha, mas deixam de funcionar caso sejam destruídos. Um cenário como o da imagem acima, portanto, embora não uma condição de derrota stritu sensu, forçará os jogadores a um impasse, impedindo que mantenham seus exércitos e consigam vencer a guerra.

O feedback dos nossos testers mostrou que o princípio foi um sucesso. Alguns membros da equipe chegaram a sugerir que os efeitos da devastação fossem “nerfados”, até perceberem que a impotência que sentiam fazia parte de um propósito: observar seu “general de poltrona” interior rapidamente dar lugar à sensação de que a guerra, como o veneno, deve ser manejada em pequenas doses.

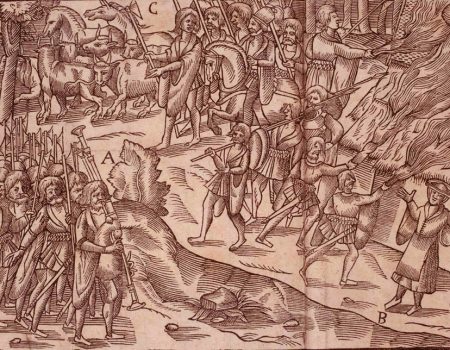

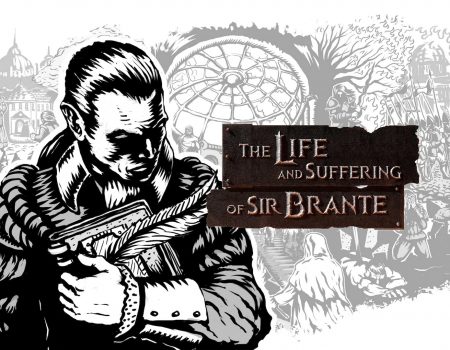

Cena de batalha da Bíblia de Holkham, de meados do século XIV

Ainda assim, nossa experiência nos deixou uma história cautelar: é preciso muito pouco para que um jogo, seguindo o caminho de menor resistência, torne-se uma apologia da guerra. Uma alta incidência de conflitos é perdoável (e, eu diria, necessária) para representações da Irlanda dos séculos XIII e XIV, em que expedições eram tão frequentes que representavam quase uma atividade anual. Porém, há muito a se perder aplicando essa lógica indiscriminadamente à história de outros lugares ou épocas.

A violência é uma muleta de game design assustadoramente eficiente.

This post is part of a series. To read the previous articles, click here

Featured image: the Ardagh Chalice, from the collection of the National Museum of Ireland. This artefact was the inspiration behind the Sam Maguire Cup offered to winners of the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. Photo by Rihani.

Games are not made exclusively of rules, fancy miniatures or boardgames with appealing artwork. While there are many definitions of what constitutes a “game” — to Civilization’s Sid Meier, they are basically a “series of interesting decisions” — many of them include two fundamental elements: ways to win — and/or, to lose.

Victory and failure conditions may seem like trivial things at first sight. From a game design perspective, however, they are anything but. The challenge is twice as hard for historical games, which need to balance the imperative of providing fun with goals that would make sense to people in the past.

As historian Robert Houghton once pointed out, it is precisely there where many commercial games are found lacking.

Everyone knows examples of games that portray past societies with a great level of polish, but allow players to act like no historical character ever would.

As I wrote in a previous post, many strategy games bow to the 4X formula (explore, expand, exploit, exterminate). To “win”, in these games, is intimately tied with growing. Oftentimes, over other players or weaker NPCs.

This logic sort of matches the ideology of certain empires in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, it cannot in any way be taken as a general law of human history.

The very act of indiscriminately annexing territory, that these games take for granted, depended on substantial logistics, military organization and political will that many past leaders lacked — and had no plans of developing.

In the period in which The Triumphs of Turlough is set, for example (1276 to 1318), Irish kings ruled over provinces that were minuscule for contemporary standards. Thomond, the game’s kingdom, barely had 3,5k km2 of territorial extent. (Sergipe, Brazil’s smallest state, is over six times bigger with 21,9k km2).

These rulers counted with armies that were rarely more than a few hundred men strong. Among these, the bulk came from the contributions of their vassals, who could simply turn against their king if he made choices of which they disapproved. Kingdoms like these did not have the conditions to wage war for longer than a few months. Nor to expand indiscriminately, absorbing more insubordinate vassals — and, with them, even more problems.

To “govern”, in this context, was less an issue of conquest and supremacy than of finding a balance between the demands one’s subjects were willing to comply with and the resources needed to dissuade one’s rivals from rebelling.

To make matters worse, this modality of low intensity warfare almost never reached any sort of conclusion. Historically, the conflicts between Clann Turlough and Clann Brian Rua for the rulership of Thomond stretched from roughly the 1260s to the 1350s. It was almost a hundred years of warfare with very little significative changes in borders or the balance of power.

How can we sell this idea to people used to games that allow us to “paint the map” with the colors of our empire? Or, if not that, with wargames in which victory and failure derive from the outcome of a single battle or campaign?

Images like the above hung above my desk (metaphorically speaking) when I started to design the rules for The Triumphs of Turlough. The solution, in my mind, required tackling two challenges. First, I would need to identify some historical outcome within the horizon of expectation of these kings and magnates that could be conceive of as a “victory”. Then, I had to “gamify” the route leading to it so that it became minimally engaging.

As our tests taught us in the most difficult way possible, neither of these issues is easy to address.

1st Attempt: febas score

If inciting players to wage war on one another could tilt the game towards a direction we did not want it to go, why not reward them for not doing it?

This idea led me to think about a score system that rewarded players for historically plausible actions. Called febas (Old Irish for “excellence”), this attribute increased every time a player took decisions that befitted a Medieval Irish king and decreased when they went off the tracks.

In this vein, winning battles, reducing the devastation of settlements under one’s control, keeping oneself prosperous and honoring agreements would increase one’s febas. On the other hand, losing battles, having settlements destroyed by other players and suffering acts of disobedience would decrease it.

At the end of the match, the coalition of Irish kings with the highest sum of febas would be declared the winner.

For the player that controlled Thomas de Clare, the English magnate in Thomond (and who, as a relative outsider to Gaelic politics, did not necessarily abide by the same playbook) the situation was slightly simpler.

Historically, the de Clares sought to consolidate their position by getting involved in the war between the Uí Bhriain. Their presence in the region depended on regular military operations and ended after a defeat in the battlefield. As such, their objectives matched the traditional logic of wargames quite well, and that allows us to borrow the genre’s victory conditions.

To win as an Irish king, therefore, one would need to accumulate febas. To win as an English magnate, on the other hand, one had to support an Irish faction in war and make sure they ended the game with more febas than their enemies.

Bunratty castle, seat of Thomas de Clare’s lordship in Thomond

In theory, this system seemed poised to succeed. In addition to discouraging players from backstabbing colleagues and acting anti-socially, the victory by febas made the game very flexible. A match, after all, could last as long as people wanted it: the score could be counted at any time, be it after a 30 minutes skirmish or an epic 3h campaign.

Unfortunately, things did not go so well in practice.

Results

What seemed to us at first the system’s greatest strength — its flexibility — proved to be its downfall. Our game, we noticed, had no clear failure conditions: it was possible to fail to win at the end of a match, never to be eliminated.

That, added to the fact that we had no turn limit, caused matches to continue indefinitely. The testers had no choice aside from keep playing until they got bored.

To make matters worse, “victory”, when it finally arrived, brought no satisfaction at all. In one of the most extremes cases, one player managed to win a match without doing absolutely anything — simply by keeping her distance from other players and avoiding getting involved in wars.

Ironically, this made some sense from a historical point of view. Bombastic climaxes and great twists of fate are common ingredients in Hollywood, not so much in human history. For a 13th century king, being able to govern in peace, with no worries other than waiting for the grass to grow, was a hallmark of a great leader.

One of our goals — to make our game as historically valid as the thesis it is based on — was starting (albeit awkwardly) to work. The problem, now, was to make it fun.

2nd attempt: Coalition victory

For our second attempt, we decided to adopt a more conventional solution.

Victory by febas had transformed our game in a kind of “king simulator”, which did not quite match the mechanics we had chosen. We had made a game that did not encourage players to wage war, but in which the only alternative to war was inaction.

To solve this impasse, we decided to abandon the simulator paradigm and bring our game even closer to wargames. To win, therefore, would specifically imply a military victory.

We decided to keep the febas score, only now as a failure condition. Diplomatic downturns and defeats in battle would slowly reduce the attribute, like a gradually diminishing hit points bar. If one’s febas reached zero, it was game over.

Febas, in this vein, would represent the political capital of one of the factions in the dynastic dispute taking place in Thomond. One (or three) lost battles would do little to determine a winner. A string of defeats, however, would soon convince the kingdom’s aristocrats that that horse had no more races left in it.

To avoid allowing the game to drag for too long, we decided that being eliminated in combat implied in the immediate loss of all febas points. The intention was to increase the risk of pitched battles, inducing players to opt for running away or surrendering, as it was customary at the time.

Implementing all of this required treating diplomacy as a much more stringent system. If in our first prototypes players were free to make and unmake alliances — in exchange for an appropriate febas penalty — in this version supporting your coalition was the only victory condition. Players could be coerced into changing sides by ceding hostages, but, if they wanted to win, sooner or later that hostage would have to go. If one started a match as a Clann Brian Rua ally, for instance, one should make sure they came out on top at the end. Whatever it took.

We had to apply a similar rigidity to warfare. Unlike the previous versions, in which players could choose when or if to start a war, conflict was now regular and mandatory. Gone were the days when a tester could win by simply staying put and avoiding neighboring conflicts.

Results

The second attempt worked much better than the first. Still, it was not bereft of issues.

The idea of making the death in combat an automatic failure condition was an immense misfire.

Far from encouraging players to avoid combat, this rule showed that it was possible to win the game in a single turn. This, by its turn, pushed players to bet everything on the battlefield.

The result were matches in which all of the concerns with logistics — originally, the main theme of the game — ended up becoming a mere prologue to the expedition phase.

Since the whole point of these mechanics was to create obstacles that appeared in the long run, this effectively made the maintenance phase meaningless: why would a player worry about enemy devastation or feeding soldiers if they could mobilize a monstrous army and win the match that very round?

Fortunately, the situation improved considerably once we removed this failure condition. In addition, this experience taught us some unorthodox pieces of wisdom.

First, these tests showed us that a broader range for player choices is not always better.

In the preliminary versions of Turlough, in which players were free to forge alliances and victory did not (nominally) depended on war, our testers felt lost. The “do whatever you want” philosophy not only prevented them from emotionally engaging with the game, but even made it harder to assimilate its logic. This is poison for a strategy game, in which the “fun” resides precisely in mastering the mechanics, anticipating problems and managing your forces in creative ways.

Second, it made us understand, at least partially, why so many games about the Middle Ages had combat-related mechanics.

In addition to the mediatic appeal of knights in shining armor, combat — and its proxies — create scenarios of direct competition that players find easy to engage with. In our case, this led us to gradually reorient Turlough so that the military conflict occupied a more prominent role than we had originally anticipated.

This did not imply in abandoning our original idea – a game about the causes and effects of warfare, rather than the war itself. Notably, the devastation mechanic works well in reining in any player that may sit at the board with imperialistic delusions in mind.

Devastation is a settlement attribute that increases every time some military activity occurs in that hex. This increase is proportional to the size of armies: the more soldiers a player mobilizes, the faster they will turn their kingdom into a pile of ashes.

Devastation tokens in the current Turlough prototype. Upside down piles (i.e. with the grey side upward) represent destroyed settlements.

Settlements are needed to feed marching soldiers, but cease to work if they are destroyed. A scenario like the one above, therefore, while not a failure state per se, will nevertheless drive players to an impasse, preventing them from keeping the armies they need to win the war.

The feedback from our testers showed that this principle was a success. Some of our team members even suggested “nerfing” the effects of devastation before they realized the sense of impotence they were facing was part of the plan: to make their inner armchair general quickly give way to the realization that war, like poison, should be handled only in small doses.

Battle scene from the Holkham bible, mid 14th century.

Still, our experience works as a cautionary tale: it takes very little for a game, following the path of least resistance, to become an apologia of war. A high incidence of conflict is acceptable (and, I’d argue, necessary) for depictions of 13th and 14th c. Ireland, in which military hostings were so frequent they constituted an almost regular yearly activity. However, there is a lot of harm to be done in indiscriminately applying this logic to the history of other places or periods.

As far as game design crutches go, violence is a terrifyingly effective one.

Comentários