Seja você um visitante de longa data ou alguém que chegou ao Finisgeekis por acaso, deve ter notado que este espaço está recheado de histórias.Algumas mais convencionais, ainda que temperadas por arroubos de sabedoria ou sensibilidade. Outras, mais difíceis – de...

Publicações

4 curiosidades sobre “Pentiment” que você provavelmente não conhecia

Nós historiadores somos famosamente chatos. É muito difícil resistir à tentação de criticar um game ambientado no passado, ainda que seja a melhor experiência que já curtimos. Pentiment é uma exceção. Ambientado na Baviera (atual Alemanha) na época da Reforma...

“Hiraeth”: morremos sozinhos, mas vivemos por meio dos outros

Hiraeth é uma daquelas palavras que vira e mexe aparece em listas de palavras intraduzíveis, ao lado de schadenfraude ou “saudade”. Tal como saudade, aliás, ela é frequentemente explicada como nostalgia, saudade de casa, tristeza de pensar em algo que é impossível ou...

Yuuta Nishio: um mangaká para as angústias de nosso tempo

Uma mulher anda de bicicleta. O terno e mochila de laptop entregam que não pedala a passeio. Um caminhão a ultrapassa. A motorista lembra alguém que conhece. Alguém importante, insubstituível. Alguém que lhe prometera construir uma vida com ela, que jamais a largaria...

“Os Triunfos de Tarlac” dev diary #9: a arte do jogo

Fidelidade histórica em jogos é um dos pontos mais discutidos por entusiastas na disciplina - Embora, como defendi em outra ocasião, não necessariamente o mais importante. Para nós, historiadores, representar adequadamente coisas como sistemas políticos,...

“A Música de Marie”: por um sonho que abrace nossa humanidade

Cerca de trinta anos atrás, algumas pessoas pensavam que a queda do Muro de Berlim seria o capítulo final de um século de catástrofes que nunca mais se repetiria. Sem dúvida, faltavam problemas a se resolver. O futuro traria sua parcela de desafios. Mas nenhum deles...

“Drive My Car”: para que serve uma adaptação?

Adaptações têm uma fama ambígua no mundo do cinema. Se é verdade que livros e filmes flertam um com o outro desde os primórdios da sétima arte, poucas opiniões são mais repetidas que a máxima “o livro é melhor”. Quando soube que o conto Drive My Car de Haruki Murakami...

“People From My Neighbourhood”: imaginação em estado bruto

Era, como diria Vinícius, um prédio muito engraçado. Famílias com exatamente seis pessoas ocupavam todos os apartamentos. Aqui e ali, coisas estranhas começam a acontecer. Um homem cuja barba cresce mais rápido do que é capaz de cortá-la. Uma pessoa cujas bolha no pé...

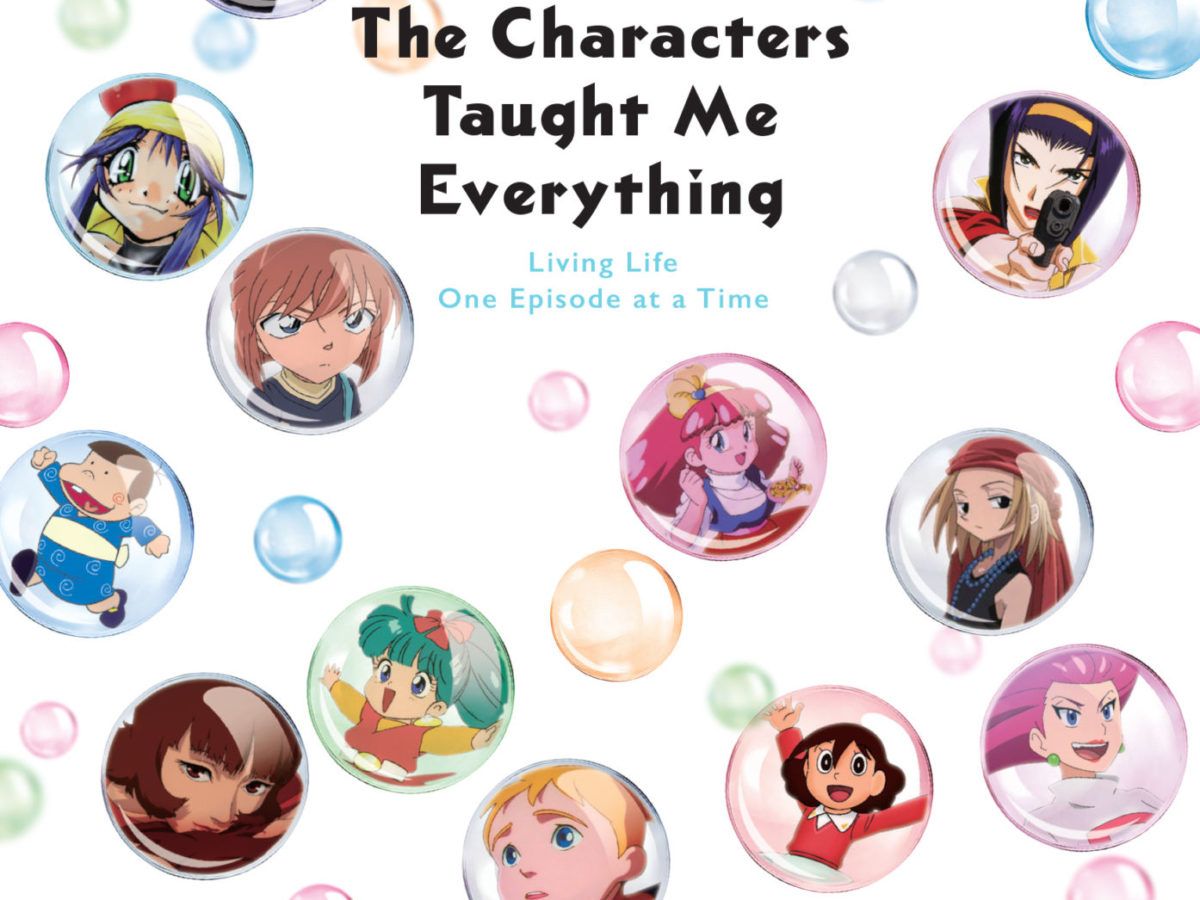

“The Characters Taught Me Everything”: por dentro da carreira de Megumi Hayashibara

Você sem dúvida já teve contato com Megumi Hayashibara, ainda que não a conheça de nome. Dubladora, cantora e radialista japonesa com uma carreira de mais de trinta anos, ela já trabalhou em alguns dos animes mais famosos de todos os tempos, como Evangelion (Rei...

O que “Mawaru Penguindrum” nos ensina sobre o extremismo

O Finisgeekis entra em mais um ano, e tenho o privilégio de anunciar algo para lá de especial. Mais uma vez, tive o privilégio de escrever para o ANN. Desta vez, sobre um tema que não poderia ser mais relevante – e um dos melhores animes já criados. Mawaru Penguindrum...

Boletim

Recebas as últimas atualizações do nosso boletim em seu email.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.