Dizia François Truffault que é impossível fazer um filme anti-guerra. Para o cineasta, o mero ato de retratar a guerra na telona já trivializa – quando não glorifica – o derramamento de sangue.

Coisa parecida pode ser dita sobre jogos. Por mais que tentemos apresentar conflitos humanos de uma maneira responsável, é inegável que a excitação de participar de batalhas é um dos principais motivos que nos leva a rolar dados e desafiar nossos amigos.

Em um jogo como Os Triunfos de Tarlac, que versa justamente sobre uma guerra, nós sabiamos que o combate era uma faceta que não poderíamos ignorar.

Felizmente, de todas as mecânicas que criamos até agora as de batalha foram as que mais rapidamente acertamos.

“Acertamos” na diversão, quer dizer. De um ponto de vista histórico, mesmo as mais cuidadosas e complexas representações da guerra são bastante problemáticas. Entender como conflitos acontecem é uma das tarefas mais difíceis para qualquer historiador. Poucas coisas são mais caóticas ou aversas a explicações lógicas que milhares de homens nervosos tentando se matar.

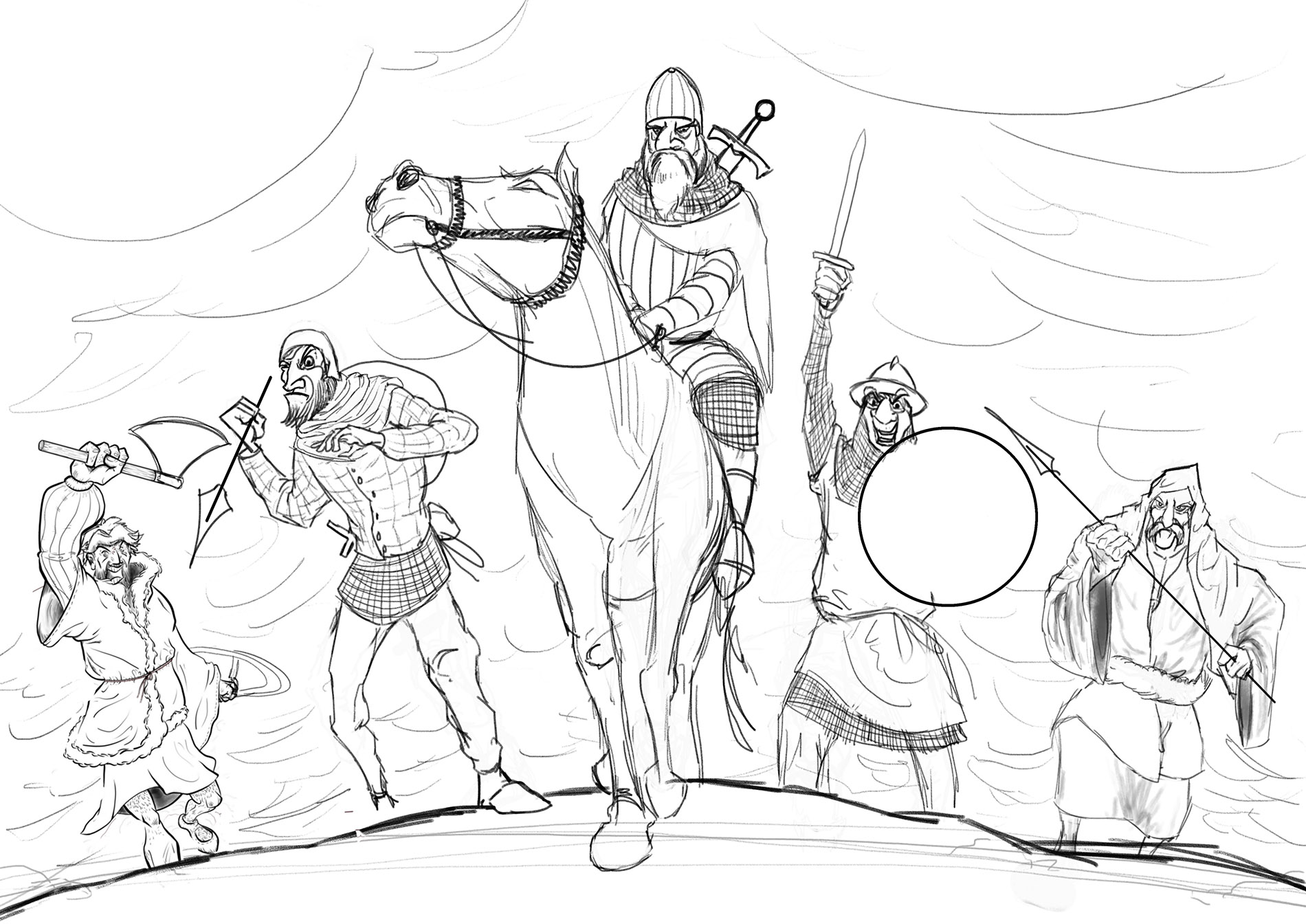

Representação artística da Batalha de Towton, 1461

Em jogos, especificamente, esse desafio significa reduzir toda essa complexidade a uma fórmula matemática.

Quando dizemos que o dano de uma certa espada longa é igual a 1d8+3 com crítico 19-20/x2, estamos justamente nos expressando por meio de uma equação. Da mesma forma, ao dizer que uma certa arma de um CRPG tem 180 DPS, estamos, no fundo, fazendo uma divisão: dano de cada ataque / número de ataques por segundo = DPS.

O desafio, para nós, é encontrar uma fórmula que respeite as particularidades da guerra medieval em vez de lançar tudo à aleatoriedade RPGística.

O combate nas guerras de Thomond, 1276-1318

Escultura da cena da paixão no Convento de Ennis, Thomond. Os soldados foram retratados com equipamento típico do final da Idade Média. Foto por Luke McInerney.

Antes de falar das dificuldades que tivemos de enfrentar, é útil explicar primeiro como a guerra do período funcionava.

Como eu expliquei no primeiro artigo dessa série, os líderes da Irlanda nos séculos XIII e XIV pertenciam a duas culturas diferentes. Parte de seu território estava nas mãos de barões ingleses sujeitos à autoridade da Coroa da Inglaterra. Outra parte continuava sob o controle de reis nativos, que cujas linhagens se estendiam para muito antes da invasão inglesa.

No papel, ingleses tinham acesso a recursos que fariam qualquer irlandês tremer nas bases. Seus guerreiros de elite, os equi cooperti (lit. “cavalos cobertos”) não tinham par no campo de batalha. A Coroa inglesa tinha mais dinheiro que qualquer reino irlandês e dispunha de uma população adulta muito mais numerosa. Qualidade e quantidade estavam a seu favor.

Equi cooperti em combate. Estes guerreiros eram assim chamados por conta dos tabardos coloridos que suas montarias usavam. Imagem: British Library Royal 16 G VI f. 379v

Na prática, a situação era outra. Na Irlanda gaélica, a maioria das populações vivia dispersa, dificultando a conquista. Não havia uma única cidade ou centro populacional que podia ser tomado, “decapitando” a administração do reino.

Entre os anos 1276-1318, quando se passa o jogo, as áreas da ilha que resistiam à conquista eram cobertas por florestas e pântanos. Nesse tipo de terreno, quase todas as vantagens táticas com que os ingleses podiam contar caíam por terra.

Cavaleiros não podiam operar livremente sob o risco de seus animais quebrarem a perna. Arqueiros tinham utilidade limitada, já que folhas e galhos obstruíam a visão e serviam de escudo natural às flechas. Armaduras pesadas, então, eram basicamente um suicídio. Guerreiros em cota-de-malha corriam o risco de afundarem na turfa.

Mesmo se os ingleses dessem sorte e conseguissem enfrentar irlandeses em terreno favorável, não era certeza de sairiam vitoriosos. Isto porque as relações entre ingleses e irlandeses não eram um Fla x Flu.

Barões ingleses viam seus pares como rivais e não tinham pudores de lutar ao lado de irlandeses se isso os beneficiasse de alguma forma. Estes aliados davam aos reis gaélicos acesso aos melhores exércitos e equipamento que o dinheiro inglês era capaz de pagar.

Nas guerras de 1276-1318, este foi o caso dos de Burgh, família inglesa que marchou diversas vezes ao lado do Clã Tarlac contra outra família inglesa, os De Clare.

Efígie do século XVI retratando William de Burgh (d.1205 ou 1206), ancestral dos de Burgh na Irlanda. Seu equipamento é similar ao que reis irlandeses na época de Os Triunfos de Tarlac usariam

Tudo isso resultava em um fato importante para entendermos o combate na época: não havia grandes diferenças de qualidade nos exércitos da época, fossem eles liderados por irlandeses ou ingleses.

Isto significa que o modelo de “tiers” de tropas com gradações diferentes de qualidade, usados por tantos jogos comerciais, não nos serviria.

Excerto de regras do board game Fief: France 1429, mostrando diferenças em qualidades de tropas

Precisávamos, portanto, de uma outra solução.

Tamanho é documento

Para nosso primeiro protótipo, elaboramos uma rolagem de combate que levava em conta apenas o tamanho dos exércitos e a sorte.

Tamanho representaria a observação histórica de que exércitos maiores costumam sair por cima. Afinal de contas, se vitórias em condições desvantajosas fossem comuns, elas não seriam tão celebradas na história militar e memória nacional.

E o fator sorte estaria aí para nos lembrar que zebras às vezes acontecem.

Calcular o tamanho dos exércitos foi a parte mais fácil. Segundo as fontes financeiras medievais, listas de baixas militares e descrições de batalhas da época, os exércitos em atividade na Irlanda eram relativamente pequenos. A maioria dos comandantes marchava para a guerra com algumas centenas de homens sob seu comando. Apenas em raros casos tropas de um único rei ou barão ultrapassavam 1000 soldados.

Assim, decidi representar esses exércitos em uma escala de 1:100. Cada ficha de exército equivaleria a 100 guerreiros até um máximo de 10 (equivalente a 1000 homens).

Esse “teto” tinha a função de evitar que jogadores “quebrassem” o jogo recrutando mais guerreiros do que seria possível a um líder da época sustentar. Outras mecânicas, como a devastação (de que falarei melhor em um diário futuro) também existem para desencorajar recrutamentos absurdos.

Esboço da arte para fichas de exército, por Vinícius de Oliveira

Implementar o fator sorte, por outro lado, foi mais complicado.

Inicialmente, estabelecemos que cada rolagem de combate seria decidida por um d6 multiplicado pelo número de fichas exércitos de cada jogador. Quem perdesse sofreria uma baixa – i.e. perderia uma ficha. Os jogadores repetiam a rolagem de combate até que um deles desistisse ou perdesse todos os seus exércitos.

Essa fórmula respeitou o princípio medieval de que exércitos grandes geralmente saíam vitoriosos. Infelizmente, ela fez isto bem demais: era virtualmente impossível para um exército menor sair por cima.

Como a rolagem era baseada em uma multiplicação, cada exército a mais que um jogador trouxesse ao campo de batalha representava uma vantagem brutal em relação ao seu oponente. Comandantes com apenas um exército, então, estavam praticamente mortos antes mesmo de lançarem os dados.

Esse era um problema que não podíamos deixar passar. A razão era simples: a batalha que selou as guerras de Thomond foi decidida graças à tenacidade de um exército pequeno.

Em 1318, o Clã Tarlac e seus aliados tinham uma vantagem numérica sobre seu inimigo, o barão Richard de Clare. Sabendo que um confronto direto acabaria mal para seu lado, de Clare desviou da capital do Clã Tarlac e decidiu atacar um de seus vassalos, o Clã Uí Dheaghaigh (em inglês, O’Dea). A ideia era destruir os irlandeses enquanto estavam divididos.

Infelizmente para de Clare, os O’Dea resistiram tempo o suficiente para que seus reforços chegassem, derrotando a coalizão inglesa.

Dysert O Dea, local da batalha que encerrou as guerras de Thomond. O castelo de mesmo nome, que pode ser visto na foto, só foi construído mais de cem anos depois do conflito.

Aperfeiçoando o fator sorte

Para acomodar esse tipo de cenário, modificamos a fórmula das rolagens. Em vez de multiplicar o resultado de um único d6, as fichas de exército determinariam o número de d6s rolados por cada jogador.

Alguém que controlasse três exércitos, assim, rolaria 3x d6; seis exércitos, 6xd6 e assim por diante.

Essa fórmula colocava muito mais a cargo da sorte, já que era possível mesmo a um jogador com rolagens de 10xd6 ter um surto de azar e tirar apenas 1s e 2s.

O resultado ficou visível nas nossas sessões de teste. Pela primeira vez desde o início das jogatinas, os membros da nossa equipe gritavam, choravam e vibravam na torcida por um dado bom ou ruim.

O problema é que, historicamente, faltavam arestas a aparar. Os resultados continuavam deterministas demais. Embora existisse uma chance real de “dar zebra”, um exército grande ainda atropelava forças menores na esmagadora maioria dos casos.

Para melhorar essa situação, decidimos nos inspirar ainda mais na matemática. Em especial, no trabalho do engenheiro britânico Frederick Lanchester.

Frederick Lanchester (1898-1946)

Durante a Primeira Guerra Mundial, Lanchester desenvolveu uma série de equações para tentar prever o resultado de batalhas.

Explicar direitinho essas fórmulas ocuparia muito espaço nesse artigo, mas uma de suas premissas é digna de nota: Lanchester insistia era que, em batalhas corpo-a-corpo, soldados tendem a lutar contra um número limitado de inimigos, mesmo que seu exército como um todo esteja em desvantagem numérica.

O fato de um exército ser 20 vezes maior que outro não significa que cada um dos soldados inimigos será atacado por 20 homens ao mesmo tempo.

É possível que uma força militar seja flanqueada ou atacada pelas costas, obrigando-a a lutar em duas ou mais frentes. Mesmo nesse caso, porém, o número de guerreiros lutando em um dado momento será quase sempre uma fração do contingente total.

Isso significa que mesmo uma força pequena é capaz de resistir a exército maior – pelo menos por um tempo. Sobretudo se ela for amparada por terreno favorável, fortificações ou simplesmente sorte.

Foi, afinal, o que aconteceu em 1318 na batalha de Dysert O Dea.

Nós decidimos aplicar esse princípio ao nosso jogo para ver o que acontecia. Segundo as novas regras, cada jogador rolaria um número de d6s equivalente ao número de fichas do jogador que tivesse menos fichas no momento do combate.

Em outras palavras, se um exército de 6 fichas atacar um de 3, ambos os jogadores rolam 3 dados.

Essa pequena mudança alterou completamente a dinâmica do combate. Números ainda eram importantes: o número de fichas de exército, para todos os fins, funcionava como “pontos de vida” de um jogador, determinando o número de rolagens que ele é capaz de perder. Desvantagens numéricas pronunciadas ( por exemplo, 10 x 1) continuam sendo uma sentença de morte. Ainda que o jogador com mais guerreiros seja incapaz de mobilizar seus 10 exércitos ao mesmo tempo, é praticamente impossível que perca no dado dez vezes consecutivas.

Por outro lado, é quase certeza que ele perderá pelo menos uma rolagem aqui e ali. O que torna as baixas mais frequentes – e o combate, muito mais perigoso.

Imagine, por exemplo, que você tenha 10 exércitos, e seus três oponentes tenham 2, 4 e 1 respectivamente. Segundo as regras antigas, sua vitória já estaria assegurada. Ainda que, por milagre, eles conseguissem se reunir para atacá-lo, você ainda teria uma vantagem de 10 x 7.

Segundo as regras novas, porém, mesmo o oponente mais fraco, com apenas uma ficha exército, pode vencer duas ou três rolagens, custando guerreiros que podem fazer a diferença entre a vida e a morte.

Não é mais necessário ter a vantagem numérica para ganhar. Mesmo underdogs podem vencer por atrito se as condições se alinharam a eles.

Obviamente, a sorte é apenas uma dessas condições. Não podemos esquecer do efeito do terreno, de obstáculos como pântanos e rios, de castelos ou mesmo de diferenças de táticas e movimentos. Soldados montados não se moviam na mesma velocidade que guerreiros de infantaria. Pequenas tropas de poucas dezenas de homens podiam cobrir terreno mais rápido que grandes contingentes acompanhados de veículos.

Mas isso tudo será assunto de um próximo diário.

François Truffault used to say that it was impossible to make an anti-war movie. According to the moviemaker, the very act of portraying war on the silver screen trivialized – if not glorified – bloodshed.

Something similar can be said about games. As much as we try to represent human conflicts in a responsible fashion, it is undeniable that the thrill of participating in battles is one of the chief reasons that makes rolling dice and challenging our friends so appealing.

In a game like The Triumphs of Turlough, which deals directly with a historical war, we knew from the outset that combat was a feature we couldn’t ignore.

Fortunately, of all the mechanics we created so far, those related to battles were the ones we had the easiest time in getting right.

By “getting right”, I mean specifically the task of making them fun. From a historical standpoint, even the most cautious and complex representations of war are very problematic. Understanding how conflicts happen is one of the hardest tasks for any historian to undertake. Few activities are as chaotic and averse to logical explanations than thousands of angry men trying to kill one another.

Artistic representation of the Battle of Towton, 1461

In games, specifically, this challenge involves reducing all of this complexity to a mathematical formula.

When we say that the damage of a given longsword equals 1d8+3 with critical 19-20/x2, we are doing no more than expressing ourselves by means of an equation. Likewise, when we say that a given weapon in a CRPG has a DPS of 180, we are essentially performing a multiplication: damage of each attack * number of attacks per second = DPS.

The challenge, for us, rests in finding a formula that respects the particularities of medieval warfare, rather than relinquishing everything to an RPG-like randomness.

Combat during the wars in Thomond, 1276-1318

Sculpture portraying a passion scene at Ennis Friary, Thomond. The soldiers were represented wearing the typical equipment of Late-Medieval Irish armies. Photo by Luke McInerney

Before talking about the difficulties we had to face, it might be useful to start by explaining how warfare worked in the period.

As I wrote about in the first post of this series, the rulers of Ireland in the 13th and 14th centuries belonged to two different cultures. Part of the island’s territory was in the hands of English barons subject to the authority of the English Crown. Another part remained under the control of native kings, whose lineages stretched back from way before the English invasion.

In theory, the English had access to resources that would make any Irish person tremble in fear. Their elite cavalry, the equi cooperti (lit. “covered horses”) had no equal in the battlefield. The English Crown had more money than any Irish kingdom and counted with a far more numerous adult population. Quantity and quality were on its side.

Equi cooperti in combat. These warriors received their names on account of the colorful caparisons worn by their mounts. Image: British Library Royal 16 G VI f. 379v

In practice, the situation was quite different. In Gaelic Ireland, the majority of the population lived dispersed around a rather large territory, making conquest difficult. There wasn’t a single city or populational centre that could be taken, “decapitating” the kingdom’s administration.

Between the years 1276-1318, when the game is set, the areas that resisted conquest were mostly covered by woods and bog mires. In this type of terrain, nearly every single tactical advantage with which the English could count meant very little.

Knights could not operate freely due to the risk of their animals breaking their legs. Archers had limited utility, as leaves and branches obstructed their vision and served as a natural shield against arrows. Wearing heavy armour was basically a suicide. Mail-clad warriors faced the risk of getting stuck in peat deposits.

Even if the English got lucky and managed to face the Irish on favourable terrain, victory wasn’t assured. This is because the relationship between English and Irish wasn’t a zero-sum game.

English barons saw their peers as rivals and had no qualms in fighting alongside Irish aristocrats if they benefitted from it in any way. These allies gave Gaelic kings access to the best armies and equipment the English money could pay for.

In the wars of 1276-1318, this was the case of the de Burgh, an English family that marched several times with Clann Turlough against another English family, the de Clare.

16th century effigy of William de Burgh h (d.1205 ou 1206), ancestor of the de Burgh in Ireland. His equipment is similar to the one used by Irish kings in the time of The Triumphs of Turlough.

All of this boils down to an important fact to understand the combat in the period: there weren’t big differences in quality between the armies of the time, be they led by Irish or English commanders.

This meant that the model of “tiers” of troops with different levels of quality, employed by so many commercial games, would not do us any good.

Excerpt from the rules of the board game Fief: France 1429 featuring differences in troop quality.

We needed a different solution.

Size matters

For our first prototype, we elaborated a combat roll that only took in account army size and chance.

Size represented the historical observation that larger armies usually came out on top. After all, if victories in unfavourable conditions were common, they wouldn’t be so celebrated in military history and national memory.

And the chance factor was there to remind us that upsets sometimes happen.

Calculating the size of armies was the easy part. According to medieval financial sources, lists of military casualties and descriptions of battles of the period, the armies in activity in Ireland were relatively small. Most commanders marched to war with a few hundred men under their command. Only in rare cases troops from a single king or baron exceeded 1000 soldiers.

Thus, I decided to represent these armies on a 1: 100 scale. Each army token would equal 100 warriors, up to a maximum of 10 tokens (totaling 1000 men).

This “ceiling” was meant to prevent players to “break” the game by recruiting more warriors than it would be possible for a ruler in the period to support. Other mechanics, such as devastation (of which I’ll talk more in future diaries) were also in place to dissuade absurd troop levying.

Sketch for the art of an army token. Drawing by Vinícius de Oliveira

Implementing the chance factor, on the other hand, proved to be trickier.

We initially established that each combat roll would be decided by a d6 multiplied by the number of army tokens each player had. Whoever lost would suffer a casualty – i.e. lose one token. Players repeated the combat roll until one of them gave up or lost all of their armies.

This formula observed the medieval principle that larger armies usually won battles. Unfortunately, it accomplished it too well: it was virtually impossible for a smaller army to come out on top.

Since the roll was based on a multiplication, each additional army a player brought to the battlefield represented a brutal advantage in relation to their opponents. Commanders with a single army token, in this scenario, were practically dead on water before they even rolled the dice.

This was a problem we could not ignore. The reason was simple: the battle that concluded the wars of Thomond was decided thanks to the tenacity of a small army.

In 1318, Clann Turlough and its allies outnumbered their enemy, baron Richard de Clare. Knowing that a direct confrontation would end bad for him, de Clare skirted around Clann Turlough’s capital and decided to attack one of their vassals instead, the Uí Dheaghaigh (in English, O’Dea). The idea was to overwhelm the Irish forces while they were divided.

Unfortunately for de Clare, the O’Dea stood their ground for just enough time for their reinforcements to arrive, defeating the English coalition.

Dysert O Dea, site of the battle that ended the wars of Thomond. The towerhouse of the same name, featured in the photo above, was only built over a century after the end of the conflict.

Revamping the chance factor

To accommodate this type of scenario, we modified the formula of the dice rolls. Instead of multiplying the result of a single d6, the army tokens of a given player would determine the number of d6s they would roll.

Someone controlling three armies, in this fashion, would roll 3xd6s; six armies, 6xd6s and so forth.

This formula placed much more emphasis on chance, as it was possible for even a player rolling 10 x d6s to have a stroke of bad luck and get only 1s and 2s.

The result was self-evident in our playtest sessions. For the first time since the beginning of our playthroughs, members of our team yelled, cried and cheered for a good or bad die.

The problem was that, historically speaking, there were still some rough edges to polish. The results were still too deterministic. While there was a real chance of an underdog getting the upper hand, a larger army still ran over smaller forces in the vast majority of cases.

To improve this situation, we decided to take even more inspiration from maths. In particular, in the work of British engineer Frederick Lanchester.

Frederick Lanchester (1898-1946)

During World War I, Lanchester devised a series of equations to try to predict the outcome of battles.

Explaining how exactly these formulae work would take too much space in this article, but one of their premisses is worth of note: Lanchester insisted that, in melee battles, soldiers tended to fight against a limited number of enemies, even if their army as a whole was vastly outnumbered.

An army being 20 times larger than another did not mean that each of the enemy soldiers would face off against 20 men at the same time.

A military force could be flanked or attacked in the rear, forcing it to fight on two or more fronts at the same time. Even then, however, the number of warriors fighting in any given moment would almost always be a fraction of the total contingent.

This makes even a smaller force capable of resisting a larger army – if only for a time. Bonus points if it has terrain, fortifications or simply chance in its favour.

It was, after all, what happened in 1318 at the Battle of Dysert O Dea.

We decided to apply this principle to our game to see what happened. According to the new rules, each player rolled a number of d6s equal to the number of tokens of the player who had the least tokens.

In other words, if an army of 6 tokens attacked one of 3, both players would roll 3 dice.

This small tweak completely altered the dynamics of the combat. Numbers were still important: for all intents and purposes, army tokens worked like “hit points” for a player, determining the number of rolls they were allowed to lose. Extreme numerical disadvantages (e.g. 10 x 1 ) were still a death sentence. Even if the player with the most warriors was incapable of mobilizing all of their 10 armies at once, it was practically impossible for them to lose in the dice 10 times in a roll.

On the other hand, it was almost assured that they would lose one roll here and there. This made casualties more frequent – and combat, way more dangerous.

Imagine, for example, that you had 10 armies and your opponents have 2, 4 and 1 token respectively. Following the old rules, your victory would be a given. Even if, by some sort of miracle, they managed to unite their forces and attack you, you’d still be looking at a 10 x 7 advantage.

According to the new rules, however, even the weakest opponent – with a single army token – could win two or three rolls, costing you warriors that could be the difference between life and death later on.

It was no longer necessary to outnumber your foes to became victorious. Even underdogs could win by attrition if the right conditions aligned.

Obviously, chance is only one among such conditions. We cannot forget the effects of terrain, obstacles such as bogs and rivers, castles or even differences in tactics and movements.

Mounted soldiers didn’t move at the same speed as infantrymen. Small warbands of a few dozen warriors could cover more ground quicker than large parties hauling vehicles.

But this is a topic for another diary.

Últimos comentários